The Minnesota Supreme Court, over a strong dissent (by Justice Anderson, joined by Chief Justice Gildea), decided recently, in a decision penned by Justice Anne K. McKeig, that Polaris, a prominent Minnesota manufacture of all-terrain vehicles, snow mobiles, and more could not withhold a report, in its entirety, from discovery in a lawsuit brought by an plaintiff who alleged he was injured in a fire caused by a defective Polaris product.

The key facts: in April, 2016, Polaris announced a product recall of a product, the RZR 900, due to fire hazard. The next month, the Consumer Safety Product Commission began an investigation into Polaris as to whether it had complied with reporting requirements. That same month, Polaris hired a lawyer, a former general counsel to the Consumer Safety Product Commission to undertake an “audit into safety processes and policies of Polaris. (See here at p.4.) In August, 2017, Mr. Colby Thompson brought a lawsuit against Polaris after he allegedly suffered serious burns when a Polaris RZR vehicle he was driving “started on fire.” Id. at 5.

The issue that the Minnesota Supreme Court had to decide: in Minnesota, is an attorney-driven undertaking like the Polaris audit entitled to a blanket “attorney-client privilege”? Or should companies, their lawyers, and courts have to parse such work line-by-line to delineate what, in such work product, is legal advice vs. what are just facts?

The Court decided that, under such circumstances, Minnesota courts should undertake a “predominant purpose test.” (See here at p. 15.) Such a test is “a highly fact-specific inquiry. Id. at 17. And the Court decided that this decision is made in the first instance at the trial court and appellate court’s review should be deferential to the trial court’s decision (using an abused of discretion standard of review). The Court went on to affirm the decision of the lower court that the predominant purpose of the safety audit was “business advice” and, therefore, the audit could not be treated as entirely privileged. Rather, the Court remanded so that the parties (and the lower court) could has out what in the audit was legal advice and what was not.

Afterthoughts: Polaris produced this audit in the litigation by mistake and sought to claw it back. Query if the outcome would have been different if Polaris had simply withheld the document from production and listed it on a privilege log.

(Minnesota Litigator answer: “Yes.”)

The document was marked “PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL: Protected by Attorney Client Privilege and Attorney Work Product” on every page. Query how the **** that slipped into the document production.

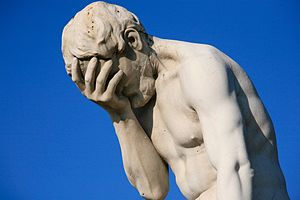

(Minnesota Litigator comment: face-palm.)